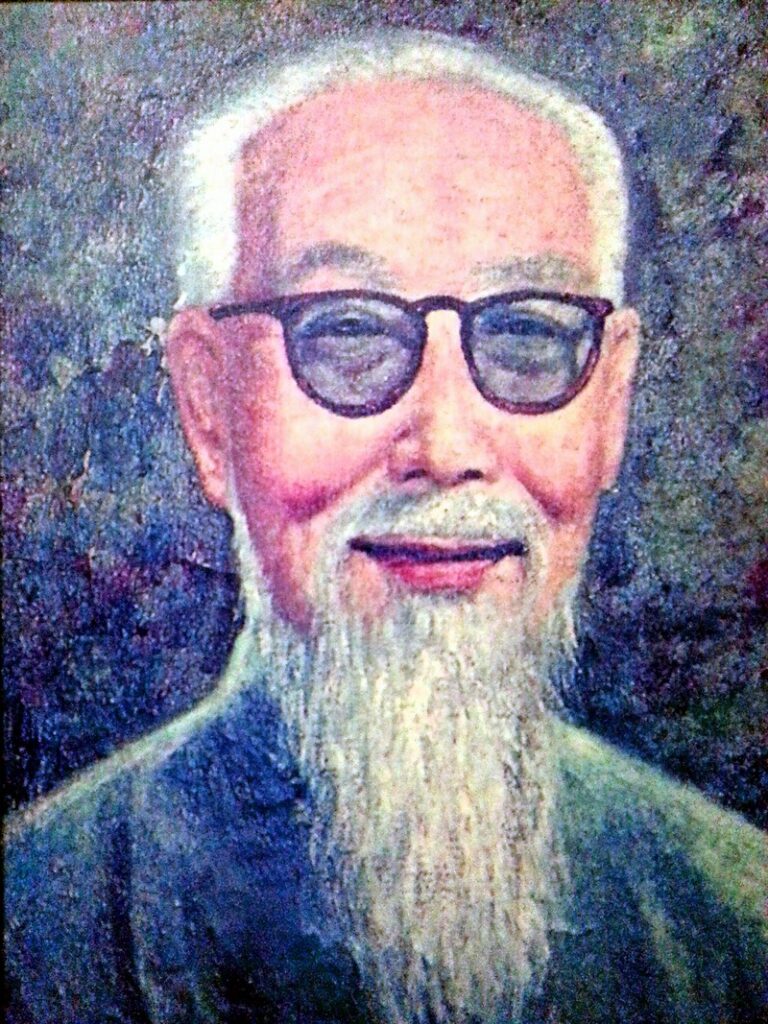

Was born in 1884, Beijing to a family of warrior-nobility in the Qing dynasty. He was very weak as a child, constantly falling sick from several illnesses. Among other things he had weak kidneys and liver cirrhosis. It was recommended that he learn Taijigong from the famed Yang family, who taught in the Imperial Courts.

That was how Wu Tu Nan started his legendary century-long relationship with Taijigong, at the age of 9. First he learned 8 years under Wu Jian Quan (disciple of the Yang and founder of Wu-school Taiji) and then 4 years of Taijigong under Yang Shao Hou. By the time he was in his twenties he was already a young master of Taijigong.

When China overthrew the Qing Dynasty, he became an archaeologist as well as librarian. He researched into Chinese ceramics and even wrote a book on it. The master artist Xu Bei Hong rendered the title The Study of Ceramics into calligraphy, but the book was never published in the tumultuous years of China..

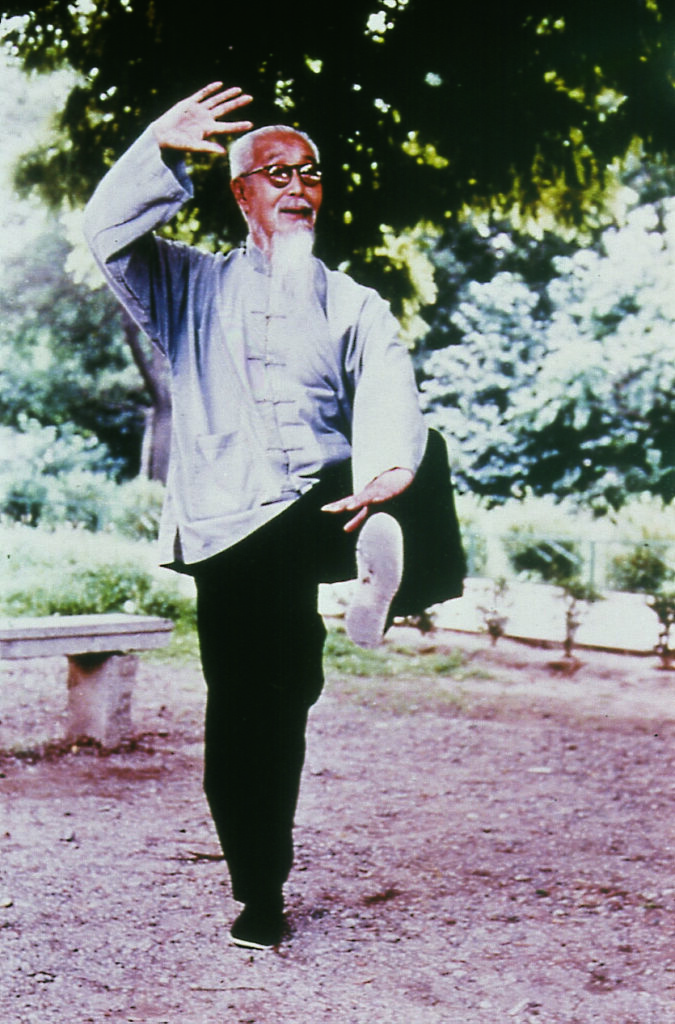

But his great love was Taiji and he started researching Taiji beyond his own lineage and became influential as a Taiji theorist, practitioner and historian.

He traveled to various parts of the country which had influenced the history of Taiji, and brought new light to our understanding of the many paths that Taiji took. He also researched into Chinese Wushu – its major lineages and main forms. All these research is now collected in The Essence of Wu Tu Nan Taijiquan and other publications.

Important too, but for a long time neglected, was his contribution and research into the spiritual and philosophical aspects of Taijigong. Before the open-door policy of the 80s, Chinese authorities frowned upon philosophy and spirituality, and this third aspect of complete Taiji, after Health and Self-Defence, was publicly ignored. But Grandmaster Wu’s private research and practice rebuilt the vanishing links between modern Taiji and the holistic legacies of traditional Chinese philosophies. These philosophies and spiritual practices drew from the Daoist Sages of Lao Tze, Chuang Tze, Zhang San Feng and Chinese Buddhism in general.

In the meantime, Taiji outside the mainland (and within as well!) was fast becoming bereft of its deeper qigong and self-defence content. New-age stylists did not understand that Taiji Self-defence was not so much about fighting but the key to self-transformation. It is through the practice of managing external forces that the Taiji practitioner learns about his own yin-yangs and the yin-yangs of his environment. Not understanding this they dismissed the deeper wushu aspects of Taiji as being irrelevant to a modern age. They watered down its contents and unwittingly emptied the art of its true potential.

At the same time, confusions about Taiji history and lineage meant that many practitioners who remained interested in the wushu aspects, sometimes borrowed from the “hard” martial arts, as they could not find good self-defnce training in watered down Taiji. This mixing of “hard” training in Taiji often also led to it being watered down from its true potential.

Wu Tu Nan’s greatest contribution therefore, was in reclaiming for Taiji its complete legacies and full potentials. And in passing it down to us in a systematic and practical way.

When he passed away peacefully in 1989 at the age of 105, he had become regarded as one of the greatest Taiji master of modern times, and lauded by both the authorities and commoners for his dedication to the art of health and well-being.

© Sim Pern Yiau 2007, 2019